A History of Lake Glenville and the West Fork Gorge

Bill Jacobs

April 2021

This piece was written for UNCA’s course entitled “History and Culture of the Southern Appalachian Region,” taught by Dr. Daniel Pierce. It blends “people” history with the ancient geologic history that created important opportunities and constraints affecting the area’s settlement and development from the 19th century into modern times.

Transitions, Remnants

and Riddles in Rock

The upper West Fork of the Tuckasegee River flows out of Lake Glenville, north of Cashiers, into a deep valley bordered on both sides by steep, forested mountains. Maybe it qualifies as a gorge, but let’s spare ourselves arguments about how much height and what angles transform a mere valley into its wilder and more romantic sibling. Whatever you call its course through the mountains, the West Fork is captivating. From Lake Glenville, its waters take seven sinuous miles to cover a straight-line distance of three, losing about 1,250’ of elevation in the process. The channel is typically 30’ or so wide, lined with overhanging second-growth forest. Most days, the water is clear and the flow is insufficient to shepherd even kayaks free of the rocks that line its bottom. Perhaps surprisingly, whether it’s clear and shallow or murky and powerful has nothing to do with recent rain patterns – which is part of the story.

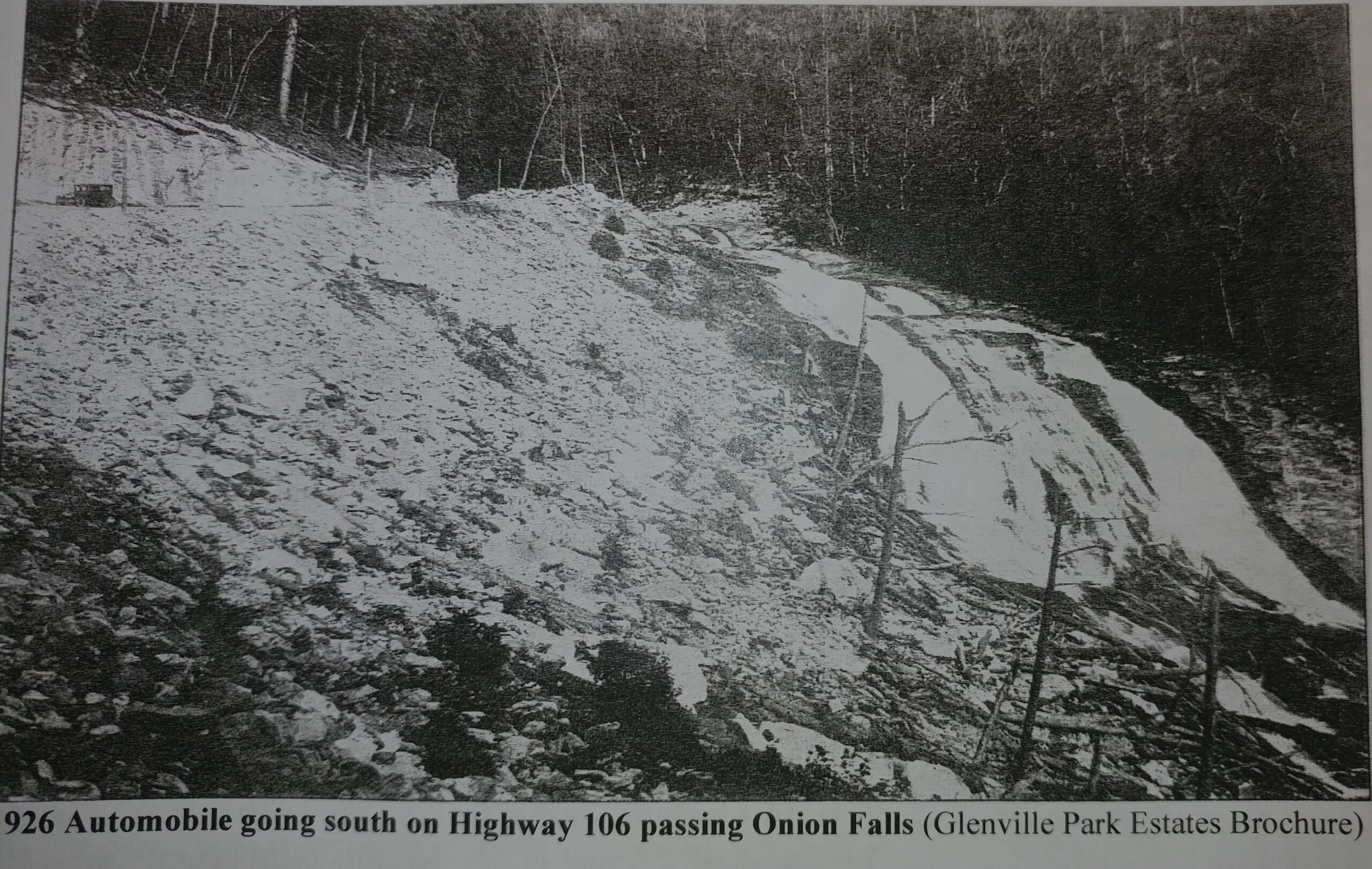

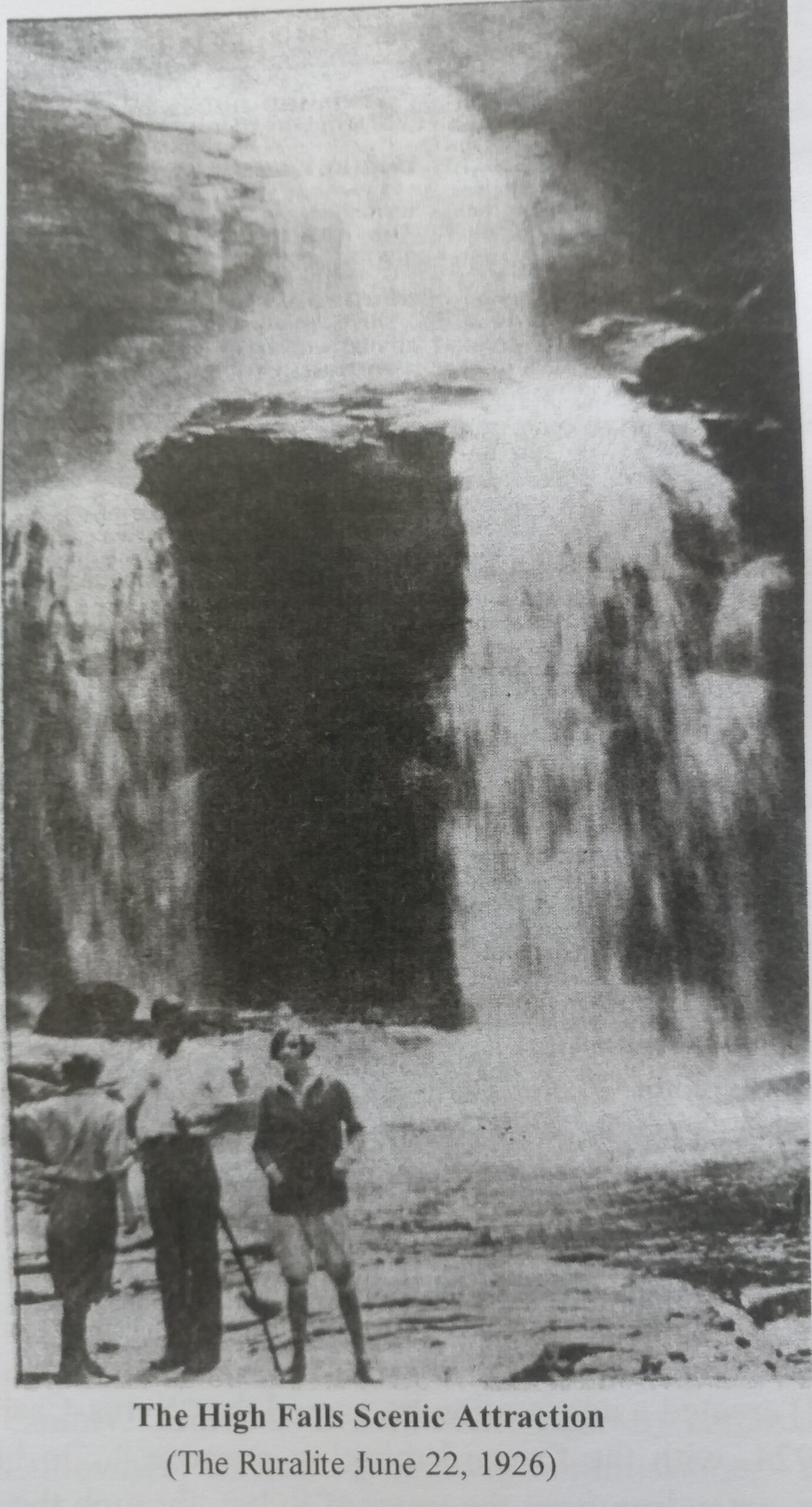

The West Fork takes two major plunges along its valley. The first, shown at right, is 200’ or so just below the Lake Glenville control gates, down a steep, slightly rounded cliff identified on the topo map as Onion Falls. The second is a half-mile further downstream, over a spectacular feature known as High Falls, comprising two 75’-ish drops in quick succession, shown below. It was this double falls, and the rocks they exposed, that first attracted my attention to the West Fork.

The rocks of the upper West Fork reveal a grand and complex transition between a family of rocks formed at the bottom of an ocean over 550 million years ago, and rocks formed more than 200 million years later. The younger rocks hardened from a large pool of molten rock trapped below the Earth’s surface, and became a granitic pluton. The older rocks (called “country rock” by geologists), tend, by virtue of their history, to be layered and fractured, so when the younger magma, hot and under pressure, arrived, it worked its away into and around the older rock in chaotic ways, particularly along the transition zone between the two types of rocks. The upper West Fork is square in the middle of that transition. The result is seen quite clearly at High Falls, in the contrast between the upper falls, with its smoothly rounded lip of pluton, and the abrupt lower falls of ragged, layered country rock. It is seen in the wide rock surface at the bottom of the falls, where the people are standing on a thin section of layered country rock, but smooth pluton extends from underneath in both directions (trust me on that one – it’s hard to make out in the picture).

As I have spent time in the West Fork and learned more about area history, I have realized that the valley’s rocks, in addition to being part of a transition in geologic history, have also witnessed, and been affected by, a sweeping transition in human history.

There is no record of European settlement in the deep valley that is home to High Falls, but above Onion Falls the valley widens and opens for a few miles before things tilt back upwards to cross the Eastern Continental Divide north of Cashiers. It was in this gentler valley that the settlement of Hamburgh (later Hamburg and, after 1881, Glenville) developed, with the first European settler arriving in 1826. In 1900, the town and surrounding

areas included about 1,160 residents. At least by 1880, it seems to have been a reasonably prosperous mountain community supported by farms and logging, although the latter’s commercial potential was limited by transportation. The roads out of the valley and down to railroads, tanneries and sawmills in Sylva or East LaPorte were long, primitive and even dangerous, with over 1,300’ of elevation difference. So, while there was logging, milling and bark (for tanning) activity, there was nothing on a scale rivaling the railroad-based logging experienced by much of Appalachia.

The rocks of High Falls did witness one early logging episode that testifies to humanity’s drive to solve problems, particularly if they interfere with income. About 1891, a then-modern sawmill was built near Sylva, with the intention of bringing in logs from along the Tuckasegee River and its tributaries, with the assistance of splash dams. Several of these were built above High Falls and attracted logs from the Glenville region. Not surprisingly, the system didn’t work very well, despite (or perhaps because of) high water flows in the then-undammed upper West Fork, augmented by splash dams. The mill closed by the mid-1890’s.

The rocks of the upper West Fork bear the scars of the next episode of expanding access to Glenville. They also pose a bit of a riddle. Revisit the earlier photo of Onion Falls, and notice the horizontal gash across its face. Why is that there? What could it possibly have had to do with building the dam high above it? The answer to the latter question is “nothing,” and to the former is that the gash is a former roadbed. Today, the main road from Sylva to Glenville and Cashiers is NC 107, running well east of Onion Falls, separated from it by a mountain. NC 107 dates from about 1940. Before that, the most direct, but very difficult, access from Sylva to Glenville was designated NC 106, and it came across the steep hill that is now Onion Falls, aiming for the nearby gap through which the river at that time flowed out of Glenville and its gentle valley. I have not been able to determine with certainty when the original primitive wagon track was upgraded to become a motor road, but it appears to have been in the early 1920’s, as the private automobile penetrated into Southern Appalachia. There were insufficient funds to pave, but an improved gravel surface and, perhaps most importantly, a secure roadbed cut into the bedrock, were provided. The accompanying photo is from 1926, and shows both automobile use and evidence of fresh blasting to create the roadbed. And that gash on today’s Onion Falls? – it leads directly into the rock wall and curve shown in the picture.

Two sidenotes are appropriate. The photo is from a promotional brochure for Glenville Park Estates, a development by a Glenville resident who divided a chunk of his land into 1,068 lots, each about 60’ x 120’, and started marketing to folks looking for their mountain dream home. Apparently 60’ is a bit short of what people had in mind, and he sold a total of 10 lots over the next 14 years. Also, the waterfall shown in the picture is the original Onion Falls, draining from what is now the bottom of Lake Glenville. We’ll come back to that in a moment.

When I walk into High Falls, I can take one of two routes. The easiest, but longest, is from the north, beginning at a connection with a lower stretch of old NC 106, crossing a ridge, then descending to the river and following it upstream along a level trail to the falls. As with so much of the mountains, I’m walking on a bit of history. In 1926, the Sylva Chamber of Commerce promoted the building of that trail to accommodate hiking and horse traffic to view the spectacle of High Falls (then also known as Tuckasegee Falls). Along the way, visitors could enjoy a higher, but not as grand, falls formed as Rough Run flows off an adjoining mountain into the West Fork.

By the 1930’s, Glenville was well along in its transition from remote mountain community to integration with the broader world in general and tourism in particular. However, the next chapter involving our rocks was more like an avalanche than a transition. In 1930, Nantahala Power & Light (at that time a subsidiary of Alcoa) began negotiations to acquire land to build Lake Glenville. Although early plans were somewhat smaller, in the end it would create a 1,450-acre reservoir diverting most of the West Fork’s water flow through a 3-mile tunnel (with short above-ground stretches of pipe) to a new power plant 1,200’ below the lake’s surface. Construction began in June 1940 (with some eminent domain valuation suits still underway). With WWII looming, it proceeded at a feverish, 24/7 pace (enabled by floodlights powered by electric lines strung for the purpose from Franklin).

At 150’, the dam created the highest-elevation power reservoir east of the Rockies. Built of locally sourced compacted soil and covering boulders, the deepest part of its base is just above the original Onion Falls and is 830’ feet thick. Readily available sources are inconsistent as to the time required for construction of the dam itself, but the formal dedication of the lake and power house occurred 16 months later, by which time the lake had completely filled (the tunnel to transport water to the powerhouse would likely have been a slow process, but it wassped up by simultaneous work from six directions on the three sections created as the tunnel emerged from the rock to cross two intervening low-lying valleys).

The town of Glenville, including about 580 graves, was relocated by about a half-mile. Most buildings and remaining timber in the lakebed were burned. A number of residents moved elsewhere, but many rebuilt. Adding insult to injury, in 1951 NP&L renamed the lake Thorpe Reservoir, in honor of its first president and the man who had spearheaded the initiative. This was corrected in 2002, when Duke Energy reverted to Lake Glenville as the official name. Today, the town’s largest businesses are involved in recreational boating on the lake.

Two remaining riddles are exposed, or perhaps answered, by the rocks. There are now two large, mostly dry, steeply plunging rock surfaces that were not visible before 1940. The first (at right), which is slowly returning to forest, tells us where the original Onion Falls, shown in the 1926 automobile picture, was located. The dam was built upstream of the falls, with its leading edge close to the falls’ lip, so it cut off the water flow but did not cover the rock – which now offers itself for some geologic exploration. The second big exposed rock surface is the new Onion Falls, shown earlier. It drains the lake’s spillway, but only a tiny fraction of the lake’s outflow goes that way, since most is diverted by tunnel to the powerhouse, and lake levels are managed to minimize spillway releases during periods of heavy rain. So why does the wide expanse of Onion Falls stay clear of intruding forest? For that matter, why does the broad rocky area at the base of High Falls stay clear?

The answer reveals a further twist in the story. In the late 2000’s, during the process for relicensing the lake for power generation, Duke Energy agreed to seven recreational releases each summer, enabling kayakers to paddle the 6 miles or so from the base of High Falls to the powerhouse. The release creates a cleansing torrent, muddy at first but quickly reestablishing a clear, fast-flowing mountain stream. The kayakers can frolic, and all of us can once again experience the grandeur of High Falls as it existed before power generation invaded the West Fork.

Duke also built a half-mile trail from the dam to the base of High Falls, with about 600’ of vertical drop.

Kayakers carry their boats down seemingly endless rocky steps to put in. At least they get to go out by water. The rest of us choosing that route have a lot of steps to climb. Perhaps the climb can be viewed as time to contemplate the transitions that so heavily affected Glenville and its residents: from a remote 19th-century mountain village, to a modest participant in turn-of-the-century industrial logging, to an early 20th-century emerging cog in the broader automobile-based economy, to the victim of overwhelming legal and industrial force as its unique setting became one more Appalachian resource exploited by the national economy, and finally to a community fully integrated with and dependent on modern tourism. These transitions track the history of Appalachia as a whole, but are unique in the details. And the scars of those transitions are present in the rocks, if you observe and know what to see.